Contributing physicians in this story

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear is a common injury to the knee with approximately 400,000 reconstructions performed annually. Most people who experience the injury report feeling a pop after making a sudden move to change directions or pivoting during sports play. Soon after the sprain (tear) occurs you experience pain and swelling around the knee. For some patients, ACL reconstruction may be the best option to fixing an ACL tear.

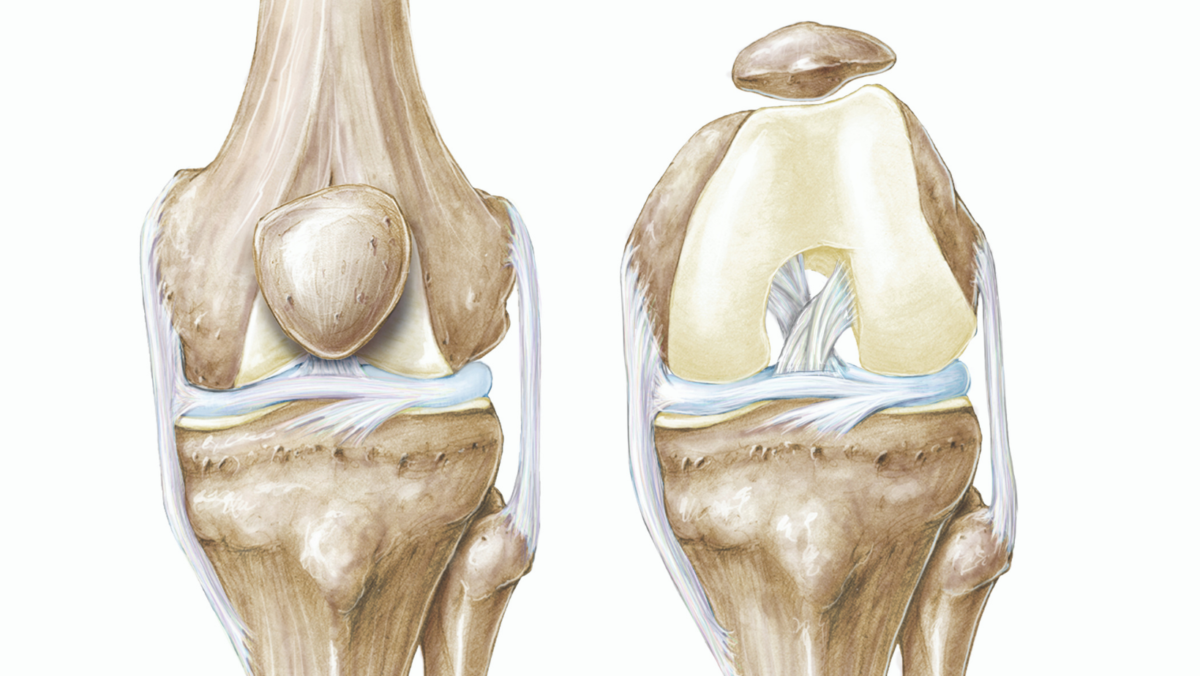

Knee anatomy

With its multiple structures and capsular attachments, the knee joint tends to be on of the most mobile joint in the body allowing for rotation, flexion (bending), and extension (straightening) during movement. The largest joint in the body, the knee is made up of the lower end of the femur (thighbone) and the upper end of the tibia, or shinbone (Fig. 1). The patella (kneecap) slides in a groove at the end of the femur.

Furthermore, the knee is a diarthrodial joint, which is characterized by the presence of a layer of cartilage that lines the ends of the bony surfaces of the femur and tibia. Cartilage inside the joint helps to cushion and absorb shock providing stability to the knee, and tendons connect the muscles to the bones. Ligaments of the knee are tough, flexible, fibrous connective tissues at the end of the femur, tibia, and fibula that connect the bones, which also help stabilize and support the knee.

Knee ligaments

Four main ligaments help stabilize the knee; the medial (inner side) and lateral (outer side) collateral ligaments resist side-to-side motion, and the anterior (front) and posterior (back) cruciate ligaments resist forward and backward motion, respectively (Fig. 1). These 2 ligaments form a cross shape with their orientation in the center portion of the knee, which is why they are termed “cruciate” ligaments. The ACL provides most of the support that prevents the tibia from slipping forward against the femur. The ligaments work together with the medial and lateral menisci (crescent-shaped cartilage) and the leg muscles to stabilize the joint and allow the knee to generate and deliver the large quantities of power required for activities.

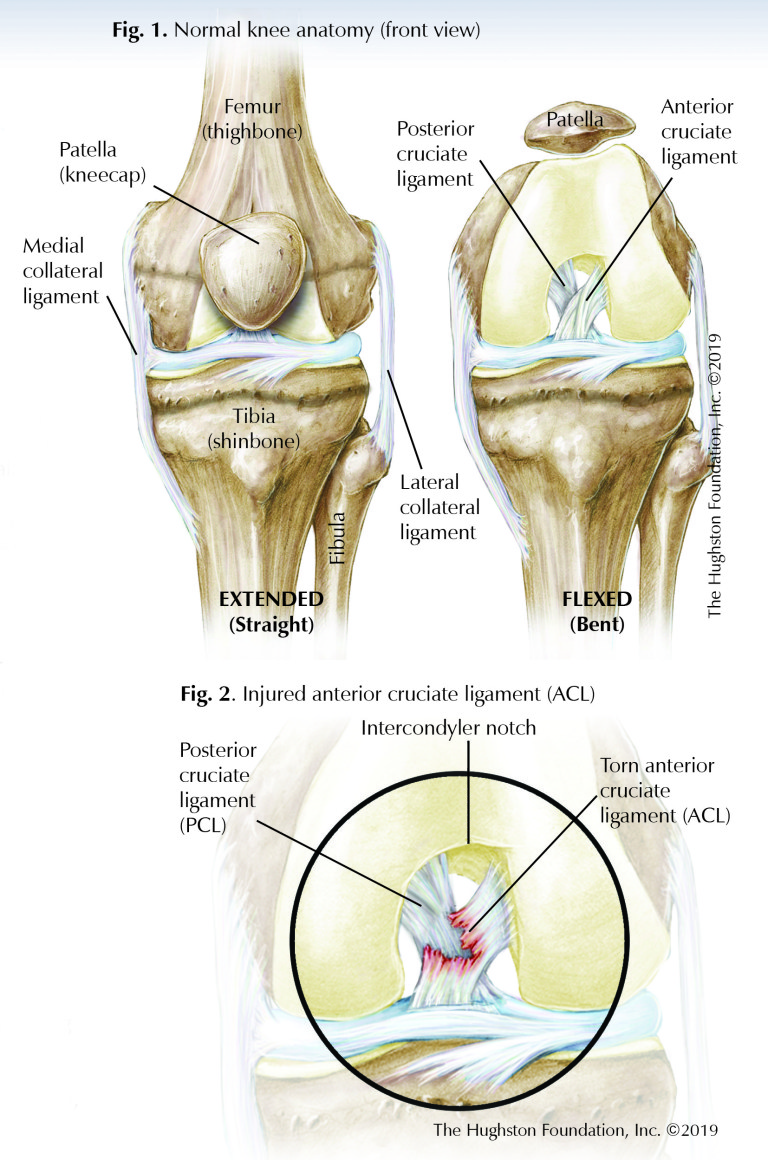

Ligament tear

During an injury to the knee, 1 or multiple ligaments may be disrupted or torn; however a tear of the ACL is one of the most common ligament injuries (Fig. 2). Partial tears are rare, so when an ACL injury does occur it is usually a complete tear. The patient often describes a feeling of a “pop” and there is usually immediate swelling of the knee. This is commonly due to a noncontact pivoting injury during a sporting event. Once an injury has occurred, it is essential to get a thorough examination, most preferably at the time of injury or soon thereafter to determine which structures have been damaged.

With today’s technology, nearly all patients with suspected knee ligament injuries undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, a scan that shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments) to fully evaluate all the soft tissue structures as well as bony anatomy to determine the extent of the injury. Once the physician has determined what structures are suffering from injury, treatment options to restore normal function can be discussed with the patient.

Nonsurgical treatment

Nonsurgical treatment can be an option for low-demand patients with decreased flexibility and those who have no feeling of instability about the knee. This treatment plan involves physical therapy, bracing, and lifestyle modifications. On the other hand, for young, active patients, or patients who continue to have episodes of instability where they complain that their knee “buckles” or “gives way” or they “do not trust their knee”, surgery is the best solution.

Weighing the pros and cons of surgery

Deciding to have surgery can be a difficult decision, especially since patients must not only weigh the risks, they must also consider the time it takes for recovery. As with any surgery, ACL reconstruction has risks and possible complications and the outcome is not guaranteed to be 100% successful. For patients who live an active lifestyle, ACL reconstruction is a good option, especially if they want an early return to sport. Additionally, the surgery helps prevent future damage to the knee cartilage and provides the best option to regain a normal functioning knee.

ACL reconstruction surgery

There have been many techniques to “repair” the ligament back to bone with sutures; unfortunately, repair of the anterior cruciate has had a high failure rate. There have also been attempts at making a synthetic ligament out of Gore-Tex, carbon fiber, and modified silk scaffolds. None of these techniques have performed well over time; therefore, the gold-standard for the treatment of an ACL tear in skeletally-mature (the bones are no longer growing) patients remains reconstruction. Especially in young active patients with persistent instability, physicians recommend that they undergo reconstruction of the ACL.

Reconstruction involves using a tendon graft, which is a piece of healthy tendon that is transplanted surgically to replace the torn ACL. The tendon graft can come from the patient (autograft) or from an organ donor (allograft). Autografts are primarily a recommendation for younger more active patients, while allografts are best for older patients. The graft can come from many different tendon donor sites to include the hamstring tendons, the quadriceps tendon, or the patellar tendon; however, the decision is often up to the surgeon’s preference and experience.

Most ACL reconstructions are done arthroscopically (a tiny camera and instruments inserted into the joint through small portals). The new ACL graft is secured into tunnels or sockets placed into the anatomic position on the tibia and the femur using a variety of techniques and devices, such as metal screws, bio-absorbable screws, suspensory fixation devices, and others with the goal to recreate a new ACL and restore stability to the knee.

After surgery

Postoperatively, patients are able to weight bear as tolerated on the reconstructed knee with the aid of a hinged type knee brace that provides stability while enabling early range of motion. Early physical therapy focuses on exercises that do not place excess stress on the graft. The goals during the first 4 to 6 weeks are to minimize pain and swelling, restore patellar mobility, restore quadriceps activation, and to normalize motion and gait pattern. During the 6 to 12 week postoperative phase, the focus is on developing strength, stability, and endurance with expected full clearance for return to sport at 6 months or beyond.

A good option for active people

ACL reconstruction using a tendon graft is a reliable and successful way to restore stability to the knee and return patients to their pre-injury activity level. If you have torn your ACL and are facing the decision on whether or not to undergone reconstruction, you should discuss your options with an orthopedic surgeon who is experienced in the surgery. Depending on your activity goals, ACL reconstruction may be the best decision for your active lifestyle.

Author: Garland K. Gudger, Jr., MD | Columbus, Georgia

Volume 31, Number 1, Winter 2019.

Last edited on October 18, 2021