The brachial plexus are nerves that conduct signals to the shoulder, elbow, and hand muscles and provide feeling in the arm. If these nerves become injured you can lose function, sensation, and experience pain. Some injuries to the brachial plexus are minor and brief, while others are severe and can cause permanent disability. These injuries often occur after a traumatic event, such as a sports injury, an automobile accident, or from complications at birth.

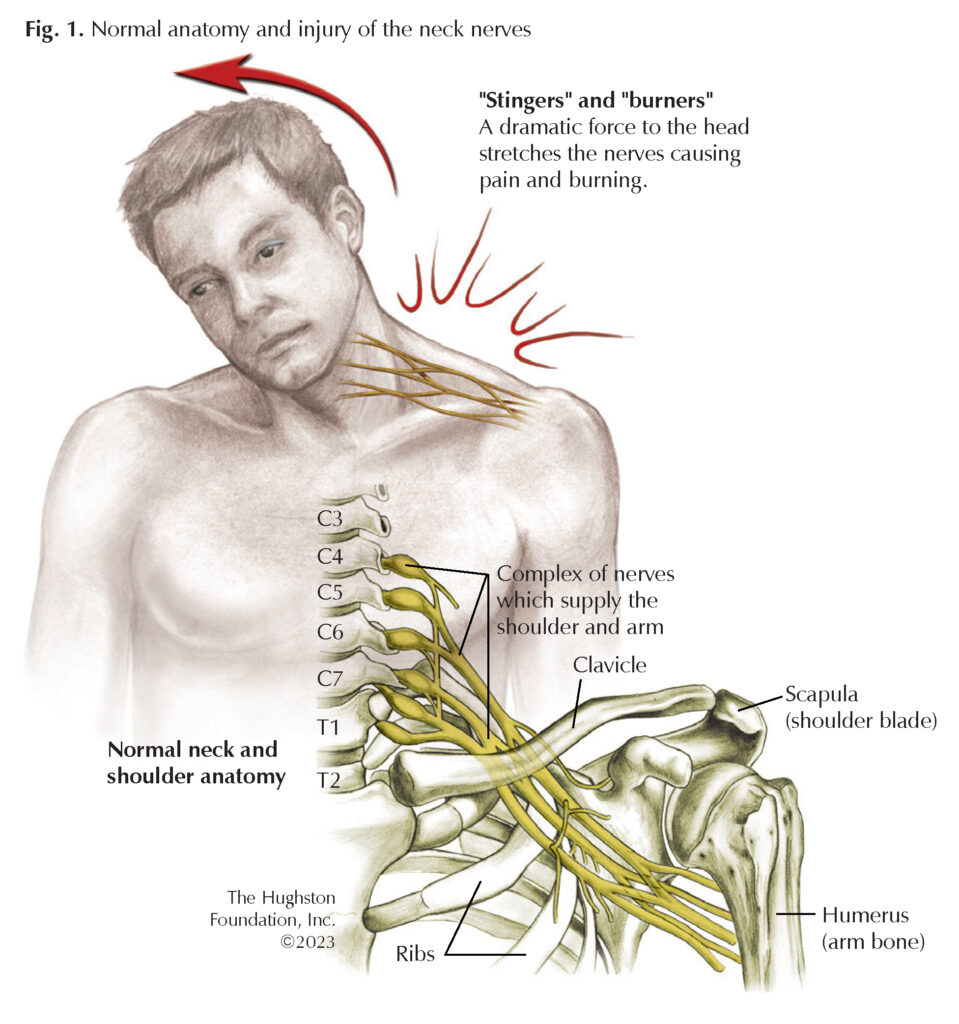

Brachial plexus injuries involve the C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1 nerves that originate from the spinal cord in the neck. As these nerves leave the neck, they form the brachial plexus, which weave together then branch as they pass under the clavicle (collarbone) toward the shoulder (Fig. 1). Depending on the extent of the injury and which nerve is damaged, brachial plexus injuries are sometimes called Erb’s palsy, Klumpke palsy, Parsonage-Turner syndrome (brachial plexus neuritis), and burners and stingers. Most brachial plexus injuries are minor and you will recover within a few weeks with limited treatment; however, other injuries can require rehabilitation or surgery and take longer to heal.

Causes

Often, brachial plexus injuries occur during high-speed automobile accidents, blunt trauma from a fall, or from the violence of a stab or gunshot wound. Difficult births are a major cause of brachial plexus nerve injuries in newborns. The nerve injuries can also result from medical conditions such as inflammation, compression from a growth or tumor, and nerve disease.

The damage occurs when 1 or more nerves are pulled, stretched, compressed, or torn. The nerve injury can be an avulsion (pulled away from the spinal cord), a stretch (pulled but not torn), or a rupture (stretched with a partial or complete tear). Often, the nerves closer to the neck are damaged when the shoulder is forced down and the nerves closer to the armpit are more likely damaged when your arm is forced upward or above your head. In addition, athletes in contact sports can sustain transient brachial plexus injuries known as “burners and stingers” after sustaining a blow to the neck and shoulder girdle region (Fig. 2). The injury occurs when the arm is forcibly pulled or stretched downward and the head is pushed to the opposite side. Interestingly, brachial plexus insult can also occur in an idiopathic (unknown cause) fashion after inflammation of the nerves.

Symptoms

For most brachial plexus injuries, only one side is usually affected and depending on the severity and location, the signs and symptoms vary. For example, the minor damage caused by a burner or stinger can produce an electric shock or burning sensation shooting down the arm and numbness and weakness in the limb. The symptoms can last a few seconds or they can last for days. Traumatic brachial plexus injuries can present with partial or complete motor and sensory paralysis of the arm, shooting pains in the affected arm, and an inability to use all or selected muscles on the affected side. These injuries can be transient and slowly resolve over time or can persist for longer periods leading to permanent damage. If you experience a serious injury, such as an avulsion, you may become unable to use certain muscles in your shoulder, arm, or hand. You may experience severe pain or lose feeling and the ability to move the limb. Acute injuries to the brachial plexus often warrant close follow-up with a medical professional.

You should seek medical advice and treatment if a brachial plexus injury is suspected, especially when symptoms persist without improvement. Additionally, you should see a doctor if you have recurrent burners and stingers, weakness in your hand or arm, or experience neck pain.

Screening and diagnosis

A thorough health history and physical exam are of paramount importance in screening patients for potential brachial plexus injuries. Your physician may first order chest, spine, or shoulder x-rays to rule out a fracture or dislocation that can cause entrapment (compression of the nerve) of the brachial plexus. Performing a computerized tomography with myelography (a CT scan using dye) a few weeks after the initial injury is the current gold standard to identify the nerve injury level. Other imaging modalities that can be useful include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography (EMG), nerve conduction velocity (NCV), and other nerve studies based on the discretion of the healthcare provider. If your physician suspects an infectious cause, he or she will include laboratory work in the screening process.

Treatment

The mainstay treatment for brachial plexus injuries remains nonsurgical management with close observation for symptom resolution. The physician conducts frequent and thorough exams over the first 3 to 6 months and performs additional testing as needed to evaluate the recovery. Partial brachial plexus injuries with a halt in neurologic resolution can require surgery. If your physician suspects an inflammatory process, a course of pain control, physical therapy, and oral corticosteroids may be necessary.

Patients with open injuries, progressive neurologic deficits, and penetrating injuries such as gunshot wounds, often require immediate surgical treatment. For patients with a total plexus injury, surgery will likely take place around 4 to 6 weeks after the initial injury.

New advances in nerve surgery are helping to restore movement and function in the shoulder, elbow, and hand, which once was impossible. There are many surgical techniques available depending on the specific injury encountered. Some of these include direct nerve repair, nerve grafting, nerve transfers, muscle or tendon (tissue connecting muscle to bone) transfers, osteotomies (bone surgery), and arthrodesis (fusion of a joint). Reconstruction procedures can take up to 3 years before full recovery occurs, especially since nerve regeneration occurs at a slow rate of approximately 1 mm/day. When comparing injuries of the upper (C5, C6) and lower (C8, T1) brachial plexus, the upper plexus tend to have better outcomes as hand function remains preserved.

Be patient

Nerves heal and regenerate slowly, so you must be patient. Your doctor may prescribe a rehabilitation program to follow to keep your muscles strong and healthy while the nerve heals. Outcomes after sustaining brachial plexus injuries are dependent on the extent and level of your injury. However, given enough time, many brachial plexus injuries heal without lasting damage.

Author: Devin W. Collins, DO | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on August 3, 2023