Dry needling, also known as intramuscular stimulation, is the use of solid filiform or “noninjection” needles to stimulate specific reactions in an area of muscle tissue and the surrounding fascia, or membrane, in order to alleviate pain. Dry needling has been a viable treatment technique for myofascial (involving the muscle and surrounding connective tissue) pain since the 1940s. At that time, Janet G. Travell (1901-1997), a physician-researcher who specialized in treating patients with myofascial pain and served as President John F. Kennedy’s personal physician, discovered that dry needling is as effective as “wet needling”—the use of hollow-core hypodermic needles to inject a fluid, such as a local anesthetic or saline solution—in relieving myofascial pain. Thanks largely to researchers like Dr. Travell, the use of dry needling has become more popular, particularly in the world of physical therapy.

How does dry needling differ from traditional acupuncture?

Dry needling neither shares acupuncture’s philosophy of treatment, which is based on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and aimed at treating the underlying causes of the pain, nor is it generally performed by an acupuncturist. (A recent Hughston Health Alert article entitled, “Acupuncture and Orthopedic Pain Management,” Volume 27 (1), reviews the current traditional Chinese style of musculotendinous acupuncture used here in the West.) In contrast to TCM, dry needling is based on contemporary knowledge of musculoskeletal and neurological anatomy, pathophysiology, and evidenced-based research. Unlike TCM, dry needling targets discrete, hypersensitive spots in the fascia of the skeletal muscle known as trigger points (a term coined by Dr. Travell in 1942). Upon palpation, trigger points may feel like nodules or knots in the muscle fibers within a taut band. Large muscles may contain clusters of trigger points. Stimulating trigger points causes local tenderness and typically reproduces the patient’s pain. It may also elicit pain in other parts of the body, a phenomenon known as referred pain.

While dry needling is distinct from traditional acupuncture, it does employ similar needles and techniques. Additionally, the trigger points of dry needling often overlap with acupuncture points as these are closely related to nerves and motor points in muscles.

Needles

Dry needling uses extremely fine, solid, stainless steel filiform needles that vary in length. The size selected for use depends on the depth of the tissue being treated. Needles should never be reinserted into a patient. Instead, single-use, presterilized, individually packaged disposable needles are recommended.

Technique

Technique

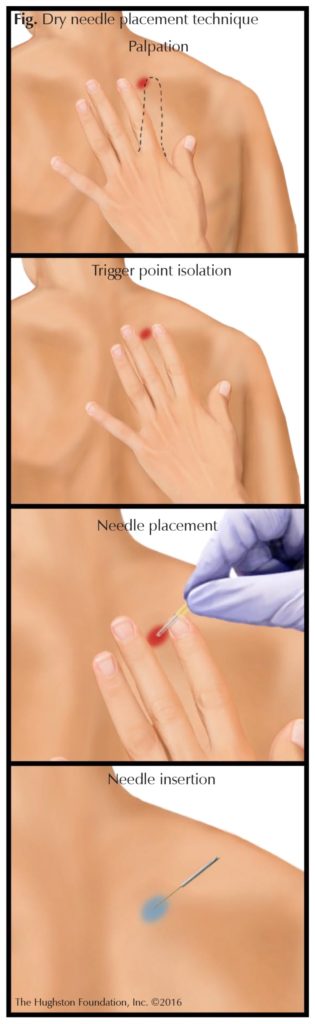

To begin insertion, the needling location is palpated and the needle placed at the specific point. Next, using a plastic guide tube, it is tapped into place; the guide tube is then removed, and the needle inserted. Once a needle is in place, the practitioner can manipulate it and adjust its depth (Fig.). Most patients describe minimal to no pain with this technique and typically report the dry needling sensation as a “light pressure.” As with most types of medical treatments, dry needling is not without risks, but the application of good palpation skills and proper technique minimize these. Possible side effects from dry needling include soreness and bruising that can last from a few hours to a couple of days.

Who performs dry needling?

Dry needling is usually performed by a physical therapist. Not all therapists, however, can offer their clients dry needling. In most states, a practitioner must have a certain amount of education and training in dry needling before he or she is certified to treat patients. Depending on state laws and practice acts, sometimes chiropractors, medical doctors, osteopathic physicians, naturopathic physicians, acupuncturists, and other practitioners are also trained in dry needling.

One tool among many

Therapists perform an initial evaluation and then use the findings to determine the proper type of physical therapy treatment for the individual patient. While dry needling can be an important part of therapeutic treatment, it is only 1 of several modalities physical therapists might use to treat myofascial pain or musculoskeletal conditions. In fact, dry needling is rarely used as a stand-alone treatment, but is usually incorporated into a regimen which can include manual soft tissue mobilization, neuromuscular re-education, posture correction, range of motion exercises, stretching, and massage, as well as ultrasound and electrical stimulation.

How does dry needling relieve pain?

The precise mechanism that makes dry needling an effective intervention for musculoskeletal pain remains unknown. Nevertheless, several theories have been formulated to explain its effectiveness by examining the response of the neuromuscular system to the introduction of a needle into the body. There are 3 types of responses: mechanical, chemical, and neurophysiological (having to do with the functions of the nervous system).

Mechanical theory

Mechanically, when a needle is inserted into the body, it damages tissue, creating a controlled lesion. The body then produces an inflammatory response to this lesion and immediately begins to work to repair the damaged tissue as well as any previous lesions in the area.

Chemical theory

Dry needling has been shown to increase the amount of chemicals at the nerve ending. The release of some of these chemicals is thought to over stimulate the nerve. The hyperexcited nerve then elicits a local twitch response (LTR) from the muscle —a visible, involuntary spinal cord reflex in which the muscle fibers contract and cause a sensation much like a cramp. The LTR works to stabilize or reset the chemical balance at the nerve ending, causing any spontaneous electrical activity to subside. This in turn “resets” the muscle and releases the local trigger point.

Neurophysiological theory

From a neurophysiological standpoint, dry needling has been shown to facilitate the release of chemicals that mediate the transmission of pain signals. Most likely, as it elicits LTRs, dry needling also activates the body’s production of endogenous opioids or pain-relieving, sleep-inducing substances, such as endorphins.

Conditions treated

Regardless of how or why it works, clinical studies comparing the effects of dry needling with placebo treatments have demonstrated that it reduces pain and improves musculoskeletal function. It has proven effective in alleviating such conditions as spinal pain, tennis elbow, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis, and other tendinopathies. Moreover, dry needling can ease muscle spasms, muscle or band tenderness and tightness, and some hypertonic (having an abnormally high degree of tone or tension) muscle conditions. It can also help to control pain following trauma, sports-related injuries, and nonsurgical interventions. Overall, it has been shown that when dry needling is incorporated into a treatment plan, musculoskeletal function is restored much more quickly. Generally, patients can expect to see positive results from dry needling after 2 to 4 sessions.

More research and more availability ahead

Despite good clinical results, many of the studies published on dry needling have lacked strong evidence because they contained small sample sizes, had high dropout rates, or were not randomized. Additional investigation and more controlled studies are thus needed to determine and document the true short- and long-term effectiveness of dry needling for various conditions.

As dry needling is still a relatively new tool, some physicians are unaware that it is available to patients.

After further research has been done, dry needling should become more widely accepted as a form of physical therapy and more frequently offered as a viable treatment option.

Author: William Kuerzi, PT | LaGrange, Georgia

Volume 28, Number 2, Spring 2016.

Last edited on October 18, 2021