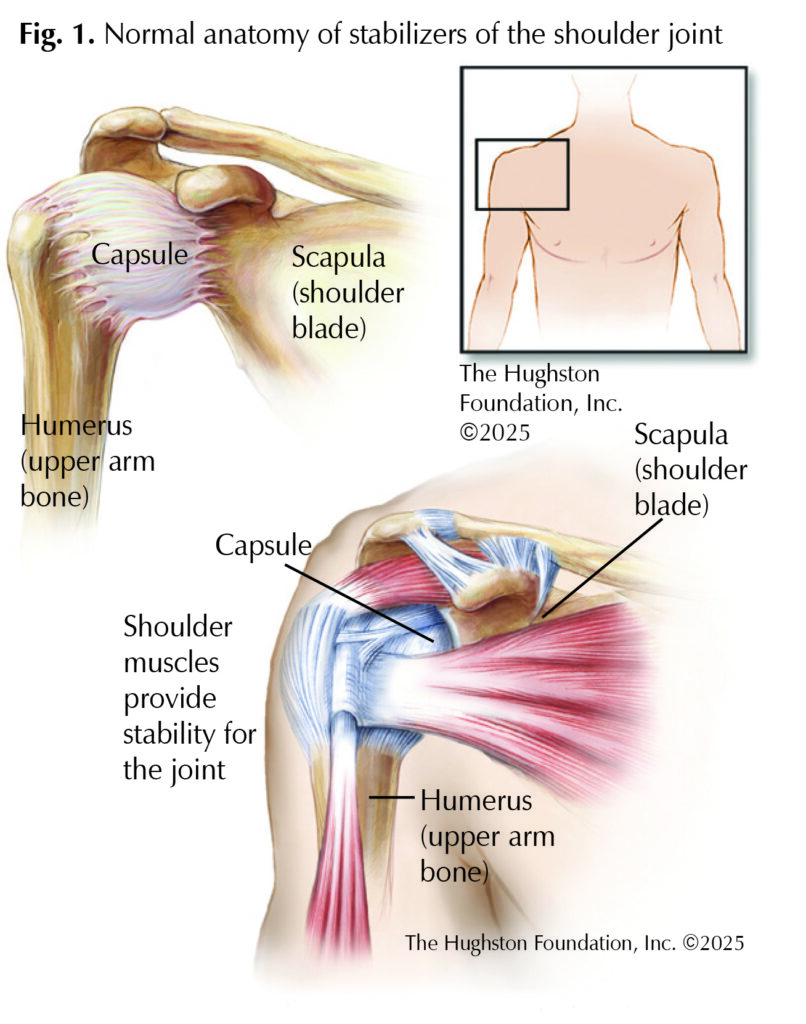

A ball-and-socket joint that connects the upper arm to the shoulder blade, the glenohumeral joint, more commonly referred to as the shoulder, has the highest range of motion of all the joints in your body. The shoulder joint allows the arm to move around in a near-perfect 360 degrees circular motion while also moving the arm outward and inward. A fibrous capsule surrounds the shoulder and seals it to keep the lubricating synovial fluid inside the joint (Fig. 1). The fluid helps reduce friction during movement and keeps the bones sliding in a smooth and painless manner. The capsule, along with your muscles, provides stability during movement. Sometimes, adhesions (scar-like tissue) form in the joint capsule, causing it to thicken and shrink. Inflammation seems to play a role, but often it’s not entirely clear why this happens. When the shoulder joint capsule becomes stiff, it can cause pain and limit your range of motion, snowballing into the disease process known as adhesive capsulitis or frozen shoulder.

Risk factors

For many patients, their physician cannot pinpoint what causes adhesive capsulitis to occur; however, certain factors increase the likelihood of the disease. Patients who are over 40 years old and female have a higher predisposition for developing frozen shoulder. Medical conditions such as diabetes, hyper- or hypothyroidism, as well as Parkinson’s and cardiovascular disease can also put patients at risk. Secondary factors can include immobility or decreased movement of the joint due to the pain of a recent surgery or injury.

Symptoms

Symptoms differ during each stage of the disease. The gradual first phase, “the freezing stage”, involves the joint capsule becoming inflamed, causing stiffness, limiting range of motion, and developing night pain. Patients often complain of a dull ache in the biceps and deltoid muscles that causes difficulty sleeping. As the capsule continues to swell, movement of the joint becomes more difficult and painful. The first stage can last from a few months to a year. The “frozen stage” follows with a decrease in pain for most patients; yet, the capsule remains inflamed and the shoulder becomes stiffer and harder to move. Normal day-to-day activities, such as dressing, cooking, or driving become difficult. This second stage can last from 4 months to beyond a year after the onset of the initial symptoms. During the third and final phase, the “thawing stage” of the disease, the inflammation begins to decrease and the range of motion starts to improve. The last stage can linger 6 months up to 2 years depending on your method of treatment.

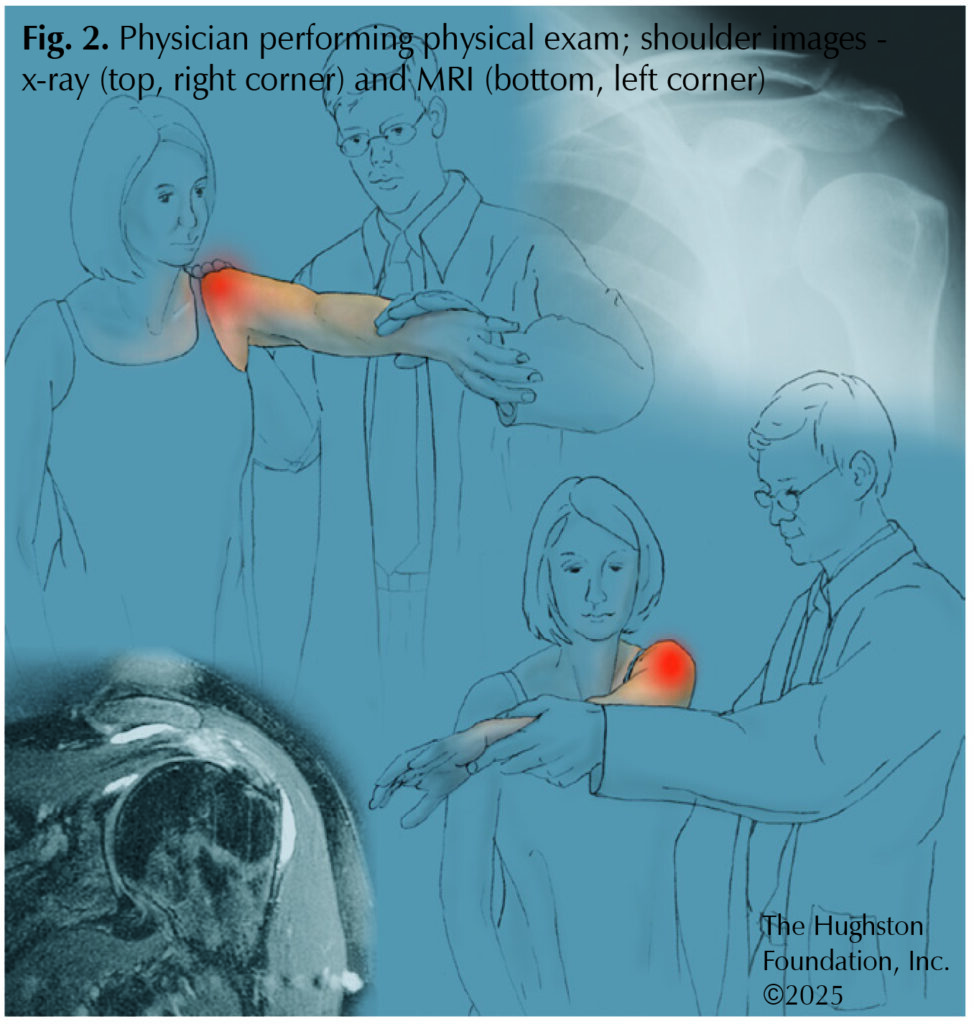

Diagnosis

An orthopaedist can diagnose frozen shoulder in the clinic by performing a physical exam, collecting medical history, and ordering imaging. The doctor will ask questions concerning the onset of symptoms, such as when and where the shoulder pain began. Exam techniques include raising your arm above your head, placing your arm behind your back, and performing internal and external rotation of the arm. The physician may stand behind you to evaluate if there is a decrease in your active and passive range of motion. If your shoulder blade rises while raising your arm sideways, it can also be a sign of frozen shoulder. The doctor may also have you lift objects to test the strength in both shoulders. The orthopaedist may order an x-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which provides detailed images of the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments of the shoulder to rule out an injury or other shoulder joint diseases, such as osteoarthritis.

Treatment

Frozen shoulder can improve on its own, but it can take some considerable time. To improve your range of motion and decrease your pain, your orthopaedist can recommend physical therapy and other nonsurgical treatments. A physical therapist can get your arm moving again and provide you with at home exercises that help strengthen the surrounding muscles and break up the fibrotic tissue in the capsule. Anti-inflammatory medications like NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and aspirin, as well as steroid injections can reduce the pain and inflammation. If the nonsurgical treatment fails to relieve your symptoms, a surgeon may need to manipulate your shoulder manually. An orthopedic surgeon can break up the fibrotic adhesions in the capsule by performing arthroscopic surgery under anesthesia.

Outcomes

Recurrence of adhesive capsulitis in the same shoulder is rare; however, some patients develop the disease in the other shoulder, roughly within 5 years of the original onset. Frozen shoulder can be a debilitating condition, but with the right care and proper treatment, you can fully recover your range of motion. However, the various types of treatment can determine how long the recovery will take.

Author: Tristan L. Melton, BSA | Columbus, Georgia

Further reading:

- Ramirez J. Adhesive capsulitis: Diagnosis and management. American Family Physician. 2019; 99(5):297-300.

- Redler LH, Dennis ER. Treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2019; 27(12):e544-e554

- Siegel LB, Cohen NJ, Gall EP. Adhesive capsulitis: a sticky issue. American Family Physician. 1999;59(7):1843-1852.

- Le HV, Lee SJ, Nazarian A, Rodriguez EK. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: review of pathophysiology and current clinical treatments. Shoulder and Elbow. 2016; 9(2):75-84.

- Date A, Rahman L. Frozen shoulder: overview of clinical presentation and review of the current evidence base for management strategies. Future Science OA. 2020;6(10).

Last edited on March 7, 2025