Contributing physicians in this story

In 1888, British surgeon J.M. Cotterill was first to describe hallux rigidus as an osteoarthritic condition of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe. Today, orthopaedists recognize this condition as the most common form of osteoarthritis (a type of joint disease that results from the breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone) in the foot. It affects roughly 2.5% of all people over the age of 50, is more common in females, and can involve both the left and right great toes. Besides arthritis, the causes of hallux rigidus include previous injury, trauma, and various deformities of the great toe, including bunion, hypermobility of the metatarsophalangeal joint, and avascular necrosis.

Anatomy

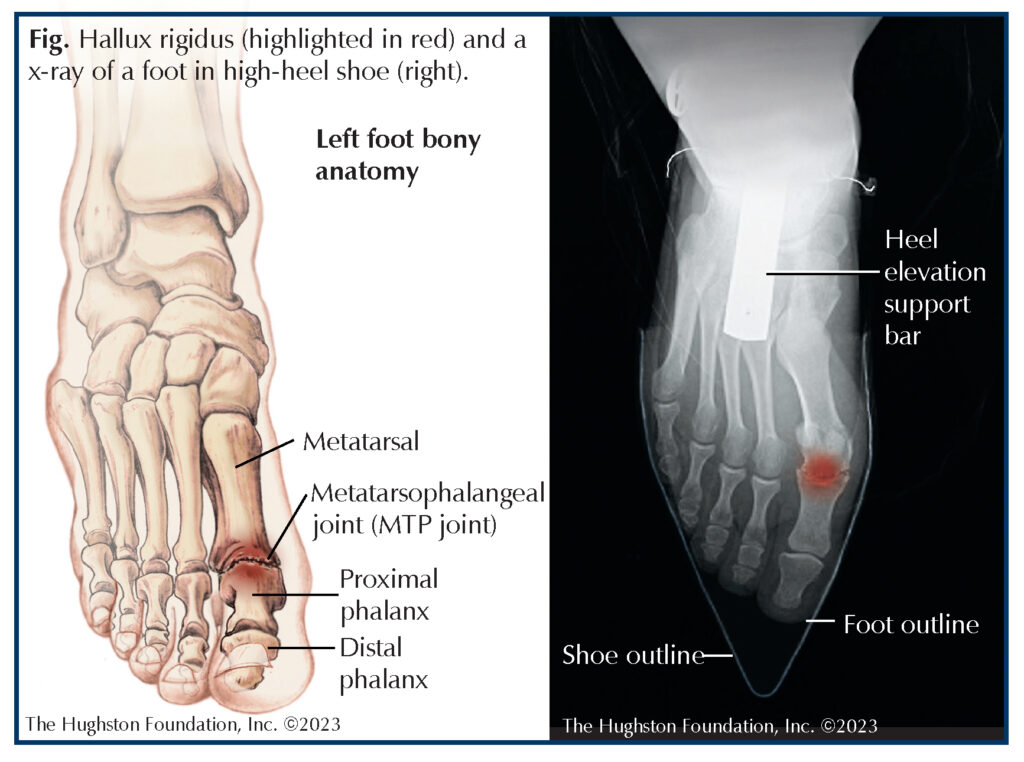

Three bones of the foot, the metatarsal, proximal phalanx, and the distal phalanx, form the great toe. The space between the metatarsal and the proximal phalanx is the first metatarsophalangeal joint, which healthcare professionals often call the MTP joint (Fig.). This joint consisting of articular cartilage (smooth tissue that covers the ends of bones) and synovial fluid (reduces friction between articular cartilage in a synovial joint) allows significant motion of the great toe. The MTP joint is also surrounded by ligaments (tissues connecting bones), a joint capsule (a dense fibrous connective tissue), and small muscles, and tendons (tissues connecting muscles to bones) that allow the great toe to move up and down. In patients who have hallux rigidus, the articular cartilage of the joint wears down causing each bone to rub together during movement. Physicians often describe this as “bone on bone” osteoarthritis. As the joint space narrows, the joint becomes stiff or rigid. The process also leads to contracture (permanent tightening) of the surrounding soft tissues.

Evaluation and diagnosis

Patients who have hallux rigidus present with painful and limited range of motion at the MTP joint of the great toe. On physical examination, the orthopaedist may find the MTP joint swollen and enlarged with bone spurs at the metatarsal head. In moderate to severe cases, patients may alter gait patterns to compensate for their pain and stiffness, especially since walking or increasing physical activity can elicit the symptoms. Patients frequently complain of difficulty wearing high-heeled shoes and joint stiffness.(Fig.)

The diagnostic imaging of choice is weight bearing radiographs (x-rays) of the foot. Depending on the severity of disease, the x-rays can demonstrate joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis (hardening of bone), deformity of the metatarsal head, and osteophytes (bony projections, or bone spurs) surrounding the joint.

Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment for hallux rigidus is often the first option offered to patients. The treatment consists of activity modification, shoe modifications, and anti-inflammatory medicines. Generally, your orthopaedist will recommend a variety of shoe modifications including a Morton’s extension orthotic, rocker bottom stiff soled athletic shoe, or shoes with high and wide toe boxes to take the pressure off the dorsal aspect of the joint. In conjunction with shoe modifications, your doctor may prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines such as ibuprofen or naproxen to help decrease swelling and pain. Additionally, your physician can recommend a corticosteroid injection into the arthritic joint space to help with pain and swelling.

Unfortunately, 2 out of 3 patients who have moderate to severe disease will fail conservative treatment. After more than 6 months of nonsurgical treatment without results, your orthopaedist may recommend surgical management as your next option. Although there are numerous surgical treatments published in the medical literature, most orthopaedists focus on 3 procedures.

The first treatment, known as a cheilectomy, is ideal for patients who have mild to moderate arthritis and pain during the extremes of motion. Cheilectomy involves removing bone spurs from the metatarsal head and removal of about 30% of the articular surface. Overall, a review of the medical literature on the procedure shows satisfaction rates of 88% to 95% with an increase in range of motion by approximately 20 degrees.

An arthrodesis or fusion of the MTP joint is the most common procedure performed for the condition and represents the current gold standard for managing severe hallux rigidus. Arthrodesis involves removing the remaining articular cartilage of the MTP joint and fusing the proximal phalanx to the metatarsal to form a single bone. Often, surgeons use a metal plate and screws to hold the fusion together. The current medical literature reports significantly high patient satisfaction scores, pain relief, and durability for the procedure. One study published in Foot and Ankle International reports the activity levels of patients after undergoing MTP arthrodesis. The study showed that preoperative activities were reestablished in 92% of patients who hiked, 80% who played golf, 75% who jogged, and 75% who played tennis.

Lastly, researchers and surgeons have developed newer orthopaedic technology regarding joint replacement surgery and synthetic cartilage. Many companies have advertised implants to replace the MTP joint of the great toe in order to preserve range of motion and provide pain relief. Medical device manufacturers make the implants from a variety of materials including metal or plastic or a combination of both. Short term studies have reported good outcomes with these implants; however, long term studies have reported high rates of implant removal and complications. Thus, orthopaedic surgeons offer this surgical option only when the patient meets strict criteria.

Seek treatment early

The management of hallux rigidus varies from conservative treatment to surgical options depending on disease severity. The key to a good outcome is to seek treatment early in the process. If you begin to experience pain and swelling and find it difficult to bend your big toe, see your orthopaedist. There are treatment options available to help relieve pain and get you back on your feet.

Author: A. Gianni Ricci, DO | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on November 15, 2023