Contributing physicians in this story

The medial ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the elbow is a small band of tissue, yet it has played a giant role in the history of sports. The media coined the name “Tommy John” 50 years ago when it brought the surgery into the limelight after the first surgical reconstruction of the UCL in 1974. Tommy John was a successful major league pitcher who thought his career was over until he had the first surgery performed by Dr. Frank Jobe. Twelve months postsurgery, Tommy John returned to the pitcher’s mound and stayed there for another 14 years.

The UCL stabilizes the elbow, especially through certain ranges of motion and stress. The ligament, located on the medial or inner portion of the elbow, runs from the humerus (upper arm bone) to the ulna (lower arm bone), deep to the flexor muscles of the forearm (Fig. 1). During normal activities of daily living, the UCL contributes very little to the elbow’s function. However, when placed under the stress of the throwing motion, the UCL has its moment, restraining the elbow from gapping open and allowing amazing acts of human performance, like throwing a 104 MPH fastball. In fact, as throwing sports demand higher and higher velocities from pitchers, the rate of UCL injuries continues to climb. Interestingly, UCL tears can occur in both amateur and professional athletes, adolescents, and veteran pitchers in their 40s. Researchers are still examining the factors that place an athlete at risk; but obviously, the volume of throwing, however measured, is the most significant contributor.

Both partial and full thickness tears can occur or the ligament can simply become thin after years of stress and microtrauma (small tears to soft tissue). Historically, patients who do not participate in heavy throwing activities can function well with a torn or deficient UCL. However, with frequent or higher velocity throwing, patients without a functioning UCL often experience elbow pain and the inability to throw at their usual velocities or with accuracy. Often, injured athletes will describe a single throw in which a “pop” was felt in the elbow; however that isn’t always the case. Patients may also occasionally sense a feeling of “giving way” or numbness of the fingers in the middle of the throwing motion.

Diagnosing the injury

Making the diagnosis of a torn UCL usually requires a physical examination and x-rays of the elbow. Some physicians use ultrasound for additional imaging during a clinic visit. Others may order a magnetic resonance imaging study (MRI, test that shows the bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments) that can confirm the presence of a UCL tear, and help the physician fully see and understand the injury.

Treatment

Until recently, tears of the UCL were treated simply with either nonoperative care through rest, physical therapy, and bracing, or surgical care with reconstruction of the torn ligament using grafted tendon. In high-level baseball pitchers, Tommy John reconstruction became the gold standard of care for many years because most athletes were able to return to play approximately 12 months postsurgery.

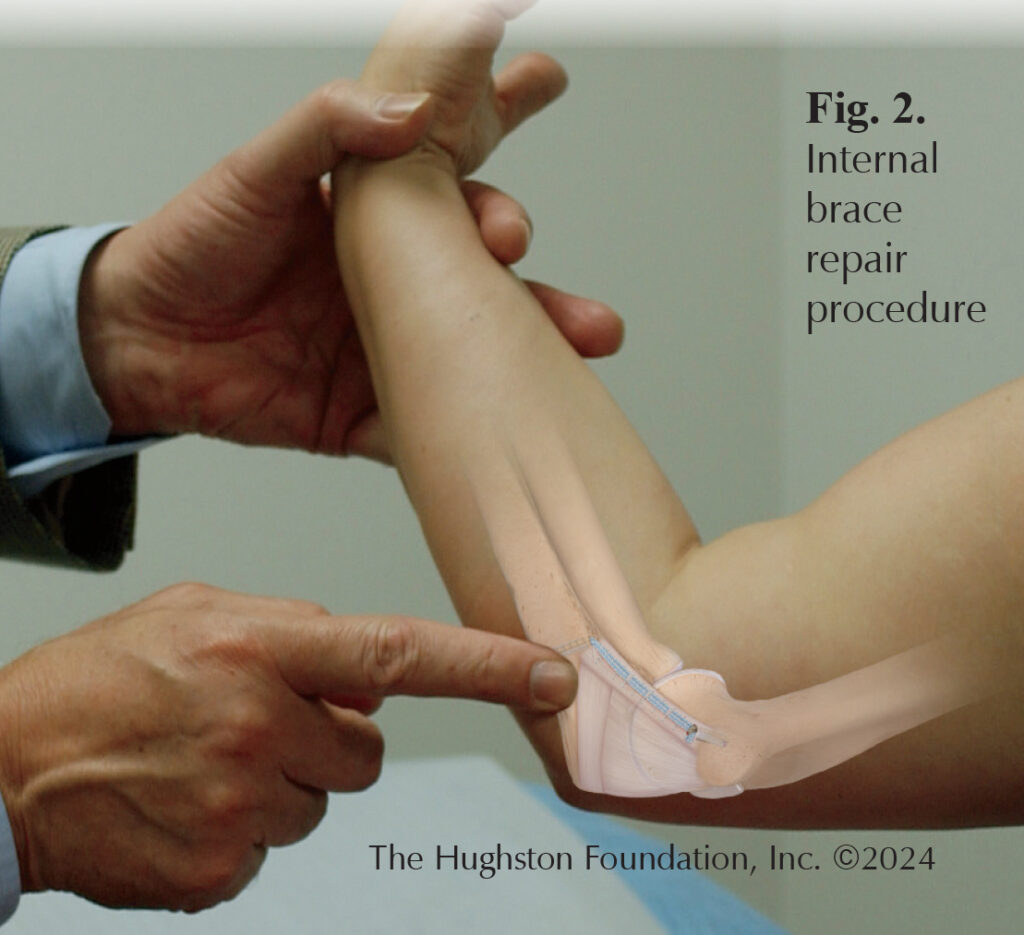

Recent innovations have added improved treatment options to the surgeon’s toolkit. Doctors have used orthobiologic treatments, such as platelet rich plasma (PRP), with some success in partial tears; however, research continues in this area. The most exciting development, however, is the internal brace repair. In this procedure, the surgeon uses specialized bone anchors and high strength suture tape to repair and then “splint” the healing ligament internally. This surgical technique allows for earlier aggressive rehabilitation and return to throwing. (Fig. 2). Some therapy protocols allow throwing progression starting as early as 3 to 4 months after internally braced surgeries.

The decision making process on how to treat UCL tears in throwing athletes can be complex, taking into account many factors such as the age and competitive level of the athlete, their position (especially in baseball), future aspirations, and other sporting activities. Also, the MRI findings and quality of existing ligament tissue may determine whether an athlete is better suited for nonoperative care, repair with internal brace, reconstruction, or some hybrid of reconstruction with the internal brace. Younger athletes with an acute injury and good ligament tissue are better candidates for repair with internal brace, while more seasoned throwers with attritional (wearing down, or weakening) tears and poor ligament quality, should undergo reconstruction with a graft. For a successful outcome, patients should consult with a skilled orthopaedic practitioner who has experience in dealing with throwing athletes.

Physical therapy

Recovery after UCL surgery often involves physical therapy, which focuses on re-establishing range of motion of the elbow and rebuilding the throwing motion of the athlete. While recovering from the surgery, often the athlete needs to correct strength deficits or imbalances in the rest of the body, which may have contributed to the UCL tear in the first place. Management of the postoperative period and decisions on return to play require a team approach, with surgeon, therapist, trainer, and coaches all in communication about the athlete’s progression. Athletes return to high-level throwing around 9 to 12 months for a ligament reconstruction, while repairs with internal bracing return closer to 4 to 6 months postoperatively.

Outcomes

The surgical outcomes for both reconstruction and repair surgery are quite good in the literature. Historically, reconstructions using traditional techniques have demonstrated a return to play rate of around 80% to 90%.¹ The newer UCL repair technique with internal bracing also has very favorable results, with 92% to 95% return to play rates.² Complications are relatively rare, but most commonly involve irritation of the nearby ulnar nerve, superficial infection, and stiffness. Overall, throwing athletes with UCL disorders seem to have a higher return to sport than those with shoulder disorders. Thus, the future of orthopaedic care for UCL looks bright, and through surgical innovation, we are now providing better care for the many throwers plagued by elbow pain.

Author: R. Lee Murphy, Jr., MD | Montgomery, Alabama

References:

- Gehrman MD, Grandizio, LC. Elbow ulnar collateral injuries in throwing athletes: diagnosis and management. Journal of Hand Surgery American. 2022;47(3):266-273.

- O’Connell R, Hoot M, Heffernan J, et al. Medial ulnar collateral ligament repair with internal brace augmentation: results in 40 consecutive patients. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021;9(7):23259671211014230.

Last edited on December 13, 2024