The forces required to fracture the pelvis of a person with normal bone structure are nothing short of massive. These types of forces are generally the result of high energy blunt trauma that occurs in extreme situations such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from heights. Approximately 8 to 10% of patients who sustain a blunt force and are treated at a Level 1 trauma center have a pelvic fracture. Because of the forces involved, pelvic fractures are often associated with trauma to organs and vessels inside as well as outside the bony pelvis. Due to the extensive blood supply to the region, they are also associated with hemorrhage (bleeding). For these reasons, pelvic fractures should never be considered in isolation, but rather in the context of a polytrauma or multiply injured patient. Furthermore, despite modern treatment techniques and advances in trauma care, acute pelvic fractures can be fatal. Fatality usually results from trauma to organs or surrounding blood vessels and nerves. Pelvic fractures can carry mortality rates as high as 50% if they are open (caused a break in the skin) and up to 20% if they are unstable. Fortunately, pelvic fractures represent only about 3% of the total number of skeletal injuries sustained in the US each year.

Anatomy of the pelvis

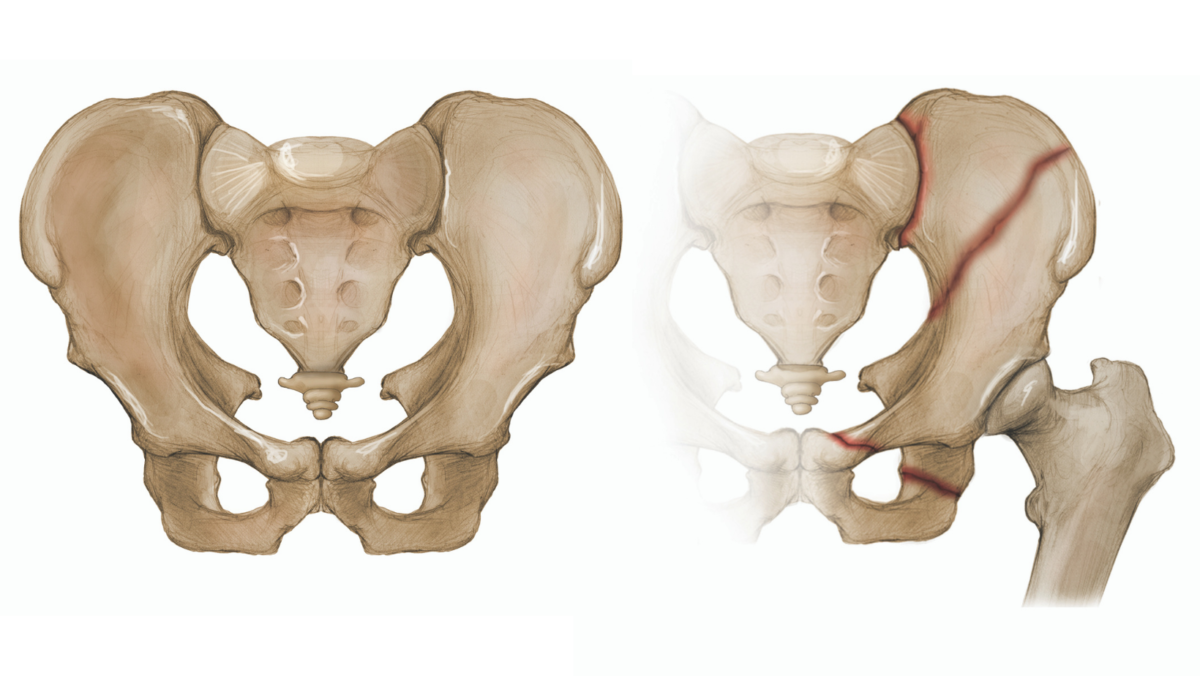

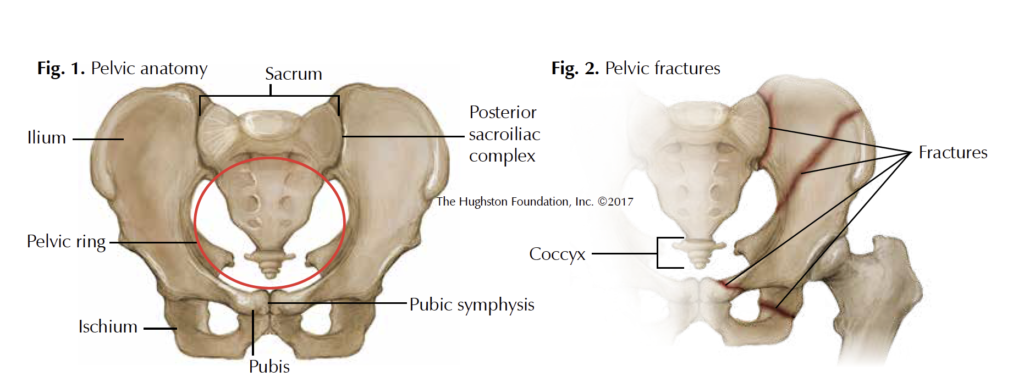

The pelvis supports and stabilizes both legs and the trunk of the body. The word pelvis is Latin for “basin,” and the bones of the pelvis form a basin or bowl-like structure called the pelvic ring. The enclosed space, which houses and protects the reproductive organs and rectum, is known as the pelvic cavity. This cavity is typically wider in women to accommodate pregnancy and childbirth. The large bone on either side of the pelvic ring is innominate or nameless. Each of these paired bones is formed by the fusion of 3 smaller bones —the ilium, ischium, and pubis—and connects to the sacrum (the bone in the lower back formed by 5 fused lower vertebrae) (Fig. 1) and the coccyx or tailbone (formed by a fusion of the last 4 vertebrae) (Fig. 2). The ilium is the broad upper portion of the bone where we place our hands on our hips. The ischium makes up the inferior or lower portion of the posterior pelvis; it is the bone on which we sit. At the anterior or front portion of each innominate bone is the pubis bone. Between the left and right pubis bone is a fibrocartilaginous disc that helps to make up the joint called the pubic symphysis (Fig. 1). This joint, together with the posterior sacroiliac complex (area where the pelvis joins the sacrum), stabilizes the pelvic ring. The anterior structure of the pelvis contributes approximately 40% of its overall rigidity, and the posterior approximately 60%. The posterior portion is thus more important than the anterior to pelvic-ring stability, which makes it also more important to pelvic fracture classification.

Diagnosis and classification

Imaging studies are needed to accurately diagnose and classify a pelvic fracture. These can include x-rays with multiple views and stress views taken while the examiner manipulates the pelvis. A CT (computerized tomography) scan featuring multiple images of the pelvis can also be done for full assessment of the fracture pattern. A careful inspection of the entire structure must be made because following a trauma, a patient often has more than just a pelvic fracture.

Fractures of the pelvis are generally classified in 1 of 2 ways. The first is based on the stability of the pelvis and includes 3 subdivisions: 1) stable; 2) partially stable; and 3) unstable. The second, referred to as the Young-Burgess classification, is based on the mechanism of injury or the direction of the injuring force applied to the pelvis. It includes 4 subdivisions: 1) lateral compression (force is applied from the side of the pelvis); 2) anterior to posterior (force is applied from front to back ); 3) vertical sheer (part of the pelvis shifts upward or downward in relation to the remaining structure); and 4) a combined mechanism.

Management

The initial management of an unstable pelvic fracture often involves applying a sheet or pelvic binder around the patient’s pelvis to compress the area and halt any ongoing bleeding from the fracture. Once the fracture patient has been resuscitated and stabilized and the injury accurately diagnosed and classified, the goal then becomes definitive treatment. The unstable pelvis must be treated early on, not only to mobilize the patient and control pain, but also to control blood clots and chronic instability or deformity. Current pelvic fracture management employs a substantial amount of percutaneous reduction and fixation. This involves making small incisions through the skin to get the fractured bones back into the correct alignment and then fixing them in place with screws applied though these incisions. The introduction of these modern techniques and treatment options has resulted in fewer pelvic reconstructive surgeries involving large open incisions, though they are still sometimes necessary to stabilize the pelvis.

Rehabilitation

The type and amount of rehabilitation the patient needs largely depend on the particular fracture pattern and the fixation obtained during surgery. For stable injuries, immediate weight bearing as tolerated is often recommended, whereas for an unstable pelvic fracture, full weight bearing is often halted for at least 8 to 12 weeks after surgical treatment.

Residual problems

Following severe pelvic fractures, almost all patients continue to experience some degree of pelvic pain. In addition, limitations in sexual and excretory (elimination) function as well as nerve injury are common. Patients should therefore be counseled appropriately. While women who have sustained pelvic injury may still be able to give birth vaginally, the rate of cesarean, or C-section, delivery is higher than for women who have never sustained such injuries.

Toward better outcomes

As pelvic fractures can be fatal and often occur in tandem with other types of traumatic injuries, they should not be considered in isolation but in the context of a polytrauma patient. Consequently, although pelvic injury classification based on overall pelvic stability and the direction of the injuring force has become more standardized, it remains only a general guide to treatment. Over the past 30 years, major advances in the ability to evaluate and treat pelvic ring disruptions have led to more individualized treatment and improved outcomes.

Author: Aaron D. Schrayer, MD | Lewisville, Texas

Last edited on October 18, 2021